Our single-stair I-Codes proposal

In April 2024, building code officials and others will meet in Orlando for the first hearing to discuss proposed changes to the International Code Council’s 2027 I-Codes, or the model building codes which are eventually adopted into law throughout the United States. As the Center for Building’s executive director, I have joined together with Scott Brody (a planner and engineer in New Jersey) and Trevor Acorn (a structural engineer in Kansas City) to submit a proposal to allow multifamily buildings up to six stories to be served by a single stair, under a strict set of conditions.

Building codes in the United States are adopted by a patchwork of states, cities, and other jurisdictions, but tend to be derived from a model code published by a nonprofit organization called the International Code Council (ICC). The ICC code that applies to American apartment buildings and other buildings larger than a townhouse or two-family dwelling is called the International Building Code (IBC). The ICC employs a staff of professionals who guide and advise participants through the code development process, but ultimately it is the members who vote and decide what goes into the model codes.

Change to building codes can follow either a “bottom-up” or “top-down” path. Modifications and innovations can start at the state or local level and, if successful, work their way up to the I-Codes and then back down into law by jurisdictions through regular code adoption cycles. They can also be accepted into the I-Codes directly, and then filter down to jurisdictions as they review and adopt the latest versions of the IBC and other codes.

Up until recently, the movement to allow mid-rise buildings with a single stair has largely taken a bottom-up approach. Provisions allowing single-stair buildings above the IBC’s three-story limit have been adopted for decades by Seattle and New York City (larger cities like these tend to be the ones most willing to modify the I-Codes, given unique built environments, highly professional fire departments, and large construction industries and building departments who can work through the challenges of code development). More recently, the consolidated City and County of Honolulu – which encompasses the entire island of Oahu, home to two-thirds of the State of Hawaii’s population – copied Seattle’s single-stair code section almost verbatim, as part of a push for more affordable housing. Over the last year or so, the Center for Building and others have worked with around a dozen jurisdictions across North America to work towards allowing multifamily occupancies up to six stories served by a single exit, as part of state and local code adoptions.

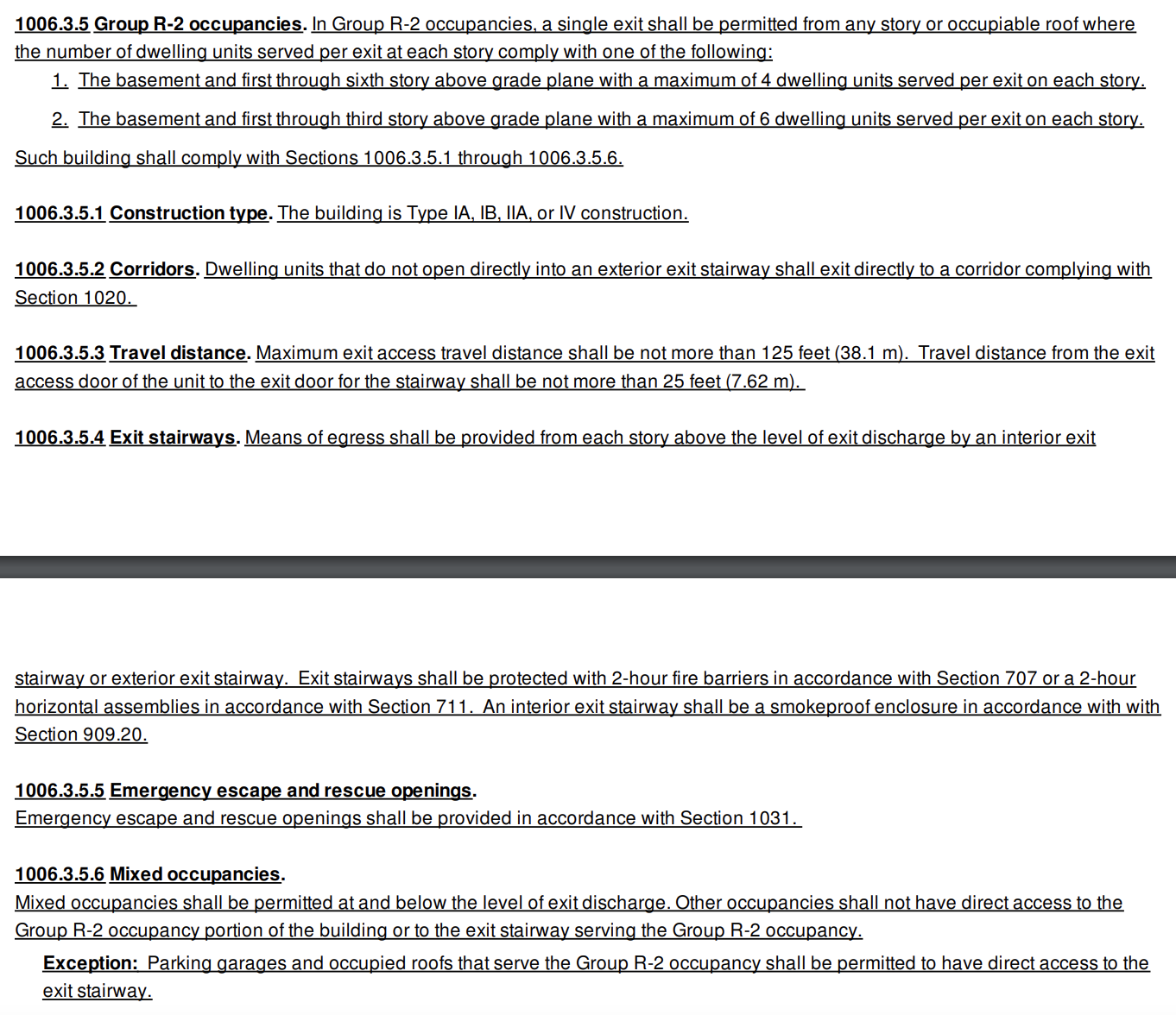

With growing interest in single-stair apartment buildings and how they can more affordably accommodate infill urban growth, we felt that it was time to propose a code change to the IBC. On page 156 (of 2,658) of the 2024 Group A Proposed Changes to the I-Codes complete monograph (or here, as a standalone document with an elaboration on our thinking attached), you can find the proposed change numbered E24-24, adding new text at section 1006.3.5, with other changes elsewhere in the text (and in the International Fire Code) to accommodate this new section.

While mid-rise single-stair buildings are unquestioned abroad, the second means of egress is a deeply held tenet of American building regulation, and any attempt to change that will face an uphill battle at the ICC. As a result, our proposal takes a more conservative approach than any other jurisdiction that has adopted anything like it.

The Seattle and New York City code sections that we took inspiration from draw from a menu of options, with some – but not all – of a range of different mitigations required in order to achieve an appropriate level of safety. New York City’s code section draws on a philosophy of passive fire safety, and Seattle’s (since copied in Honolulu) places more emphasis on active systems.

New York City has, since early 19th century rules against wood-frame construction, followed the European fire safety approach of building primarily out of noncombustible materials while being more permissive about other elements, and its single-stair code section reflects that. It limits the structure of single-stair residential buildings to types I and II construction, and imposes a height limit of six stories and an upper floor plate size of 2,000 square feet. Beyond that, it does not require any particular mitigations. The city has never adopted the IBC’s requirement to install full NFPA 13 fire sprinklers in residential buildings up to six stories (instead allowing lower-cost NFPA 13R systems), and also never adopted the IBC’s requirement to protect elevator hoistway openings on residential floors with smoke curtains, elevator lobbies, or mechanical pressurization.

Seattle has historically sat on the other end of the spectrum, with a history of permissiveness towards wood, and compensation with active fire protection systems. This more American approach has manifested itself in a single-stair code section that places no limits on construction type beyond those found in the rest of the code, but a requirement to use full NFPA 13 sprinklers (even at heights where 13R systems would otherwise be allowed) and pressurization (or exterior placement) of both the stair and elevator shaft. Seattle is more permissive than New York City towards floor plate size, allowing four units per floor and travel distances from the farthest corner of the unit to the stairway of up to 125 feet.

Our proposal combines elements from both for a more stringent overall set of conditions. We require construction to be of types I, II-A, or IV (in layman’s terms, concrete, steel, or mass timber), while at the same time requiring stairway pressurization. We leave the IBC’s ordinary sprinkler requirements in place (somewhat closer to Seattle’s stricter conditions than New York City’s), and adopt Seattle’s floor size limits.

In addition to being more stringent on the whole than Seattle, Honolulu, and New York City’s codes, our proposed code section is dramatically more restrictive than rules found in other high-income countries. Our buildings will be smaller in both height and floor plate size (abroad, single-stair apartment buildings can go up beyond 30 stories, and have six or more units per floor), they will have more protected stairwells (in other countries, apartments typically open directly onto the stair landing at these low heights), and they will have sprinklers (which are almost unheard of in Europe and Asia for a mid-rise building).

The proposal we’ve set forth is meant to be a starting point for a conversation about single-stair buildings in the American context. American building code and fire service officials will likely view it as an overly permissive proposal to be watered down. Developers and those with more international perspectives, on the other hand, may see it as overly stringent. Current prescriptive codes (both in the United States and abroad) have been essentially handed down over the years and modified through trial and error, with less engineering and research than one would hope for in such important regulation. As such, we expect our understanding of the issue to evolve over time, as the topic is debated and more research is conducted.

Along with our proposal, we have written a 17-page “reason statement” as is typical in the ICC process for major code change proposals, which can be found at the end of our proposal here. In it we address questions about firefighting operations, egress, realistic alternative site uses, fire loss history, and major fires like the 2017 Grenfell Tower fire in London. If you are interested in discussing our proposal or have any questions, please email me at stephen@centerforbuilding.org.