Why we can’t build family-sized apartments in North America

In February, I, along with real estate developer Bobby Fijan, went on the Bloomberg podcast Odd Lots to talk about why it’s so hard to find a family-sized apartment in the United States. I argued that North American zoning and building codes work together to drive up the size of multi-bedroom apartments in particular, putting them financially out of reach for many parents raising children. In other words, even if developers built more two-, three-, and four-bedroom apartments, you probably wouldn’t be able to afford one, because they would have to be so much larger than units with the same number of bedroom in Europe or Asia.

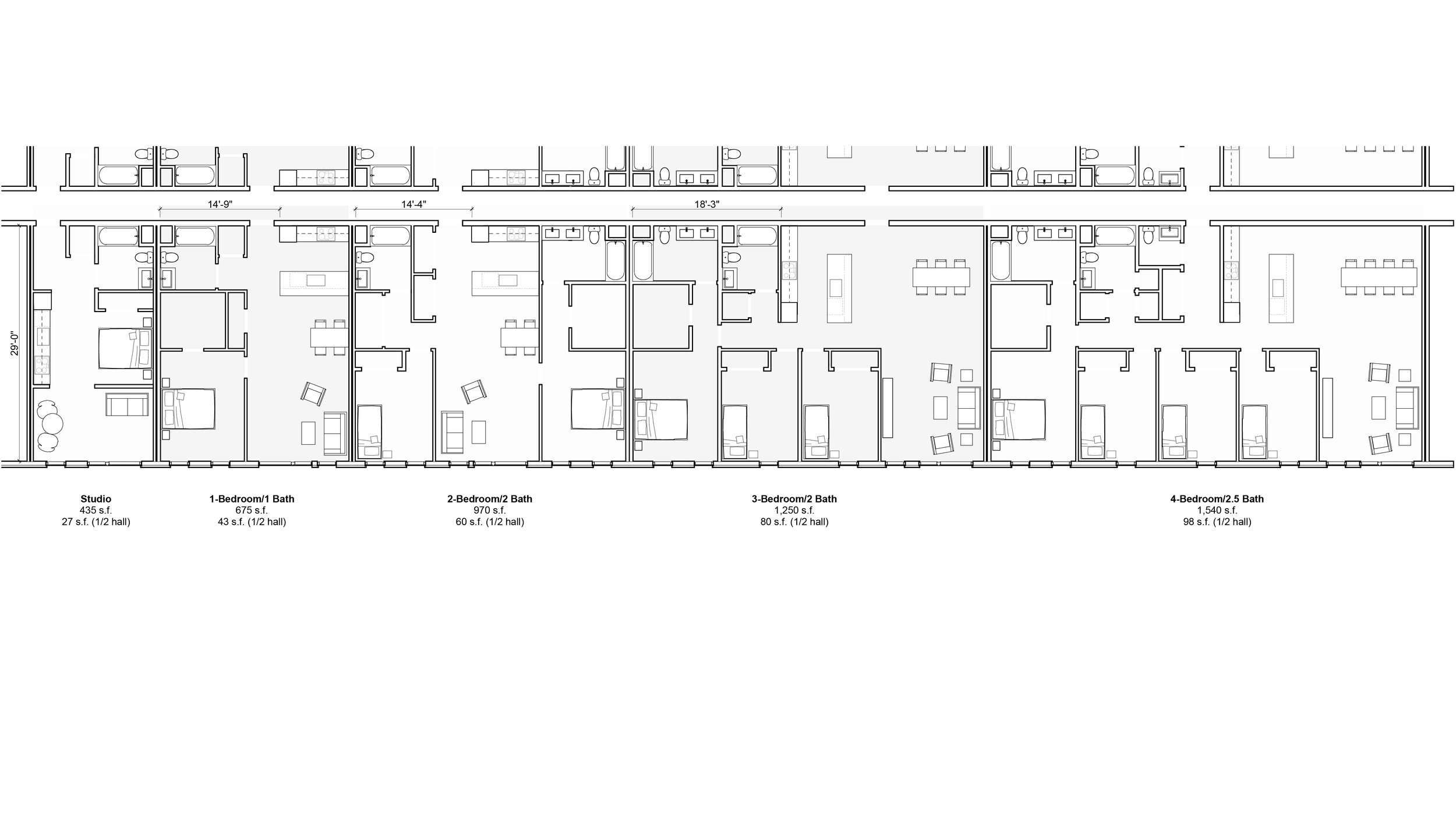

This is fundamentally an issue of space, and it’s hard to convey over a podcast. So I worked with architect and Center for Building board member Michael Eliason – founder of Larch Lab, which introduced many North Americans to the concept of point access block apartment buildings – to visualize the problem. He drew some floor plans for apartments built to North American codes, and then a few built to more European codes. The plans show how, as a North American architect tries to add bedrooms, the size – and therefore cost – of the apartment balloons faster than it would in a point access block design in Europe or Asia.

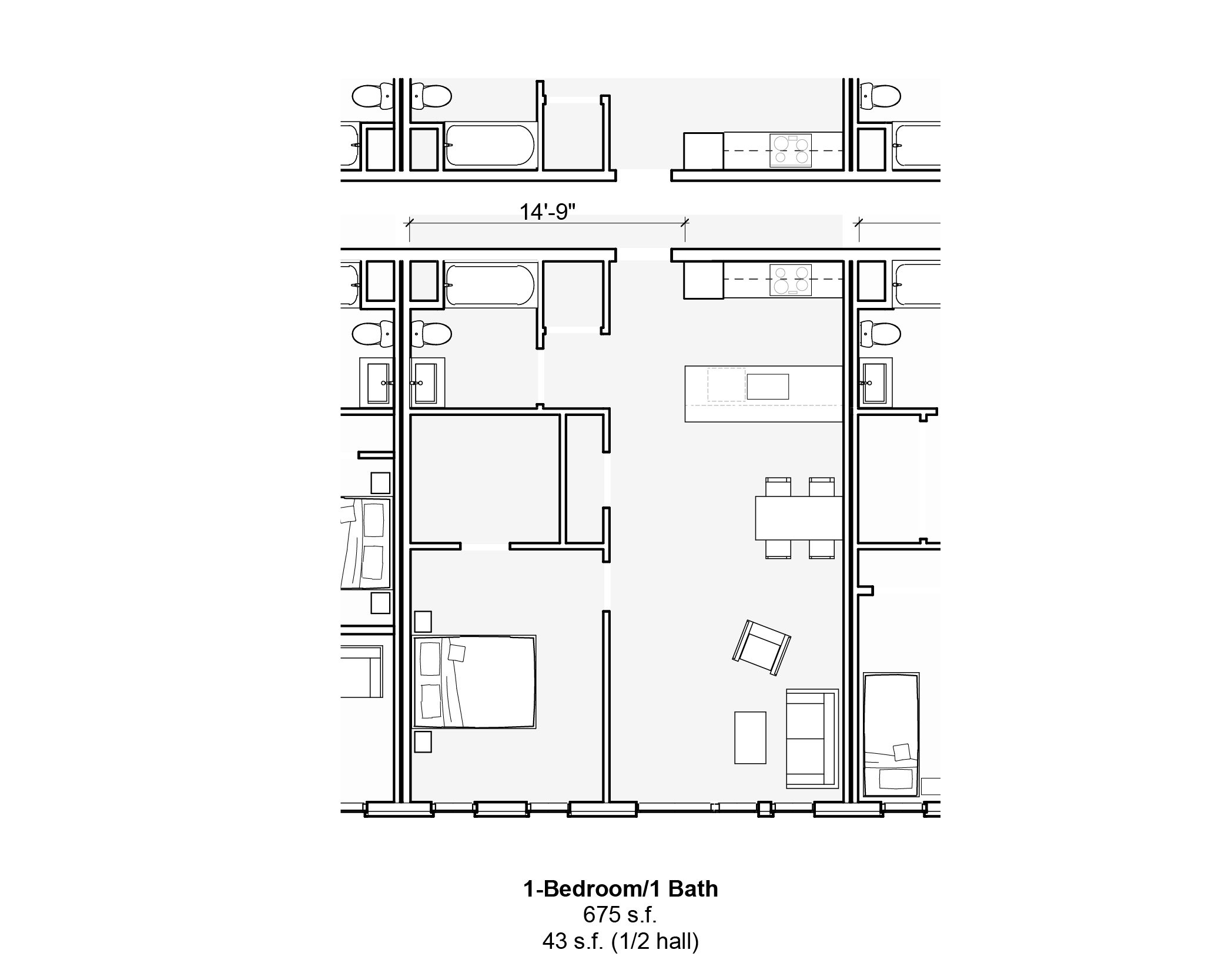

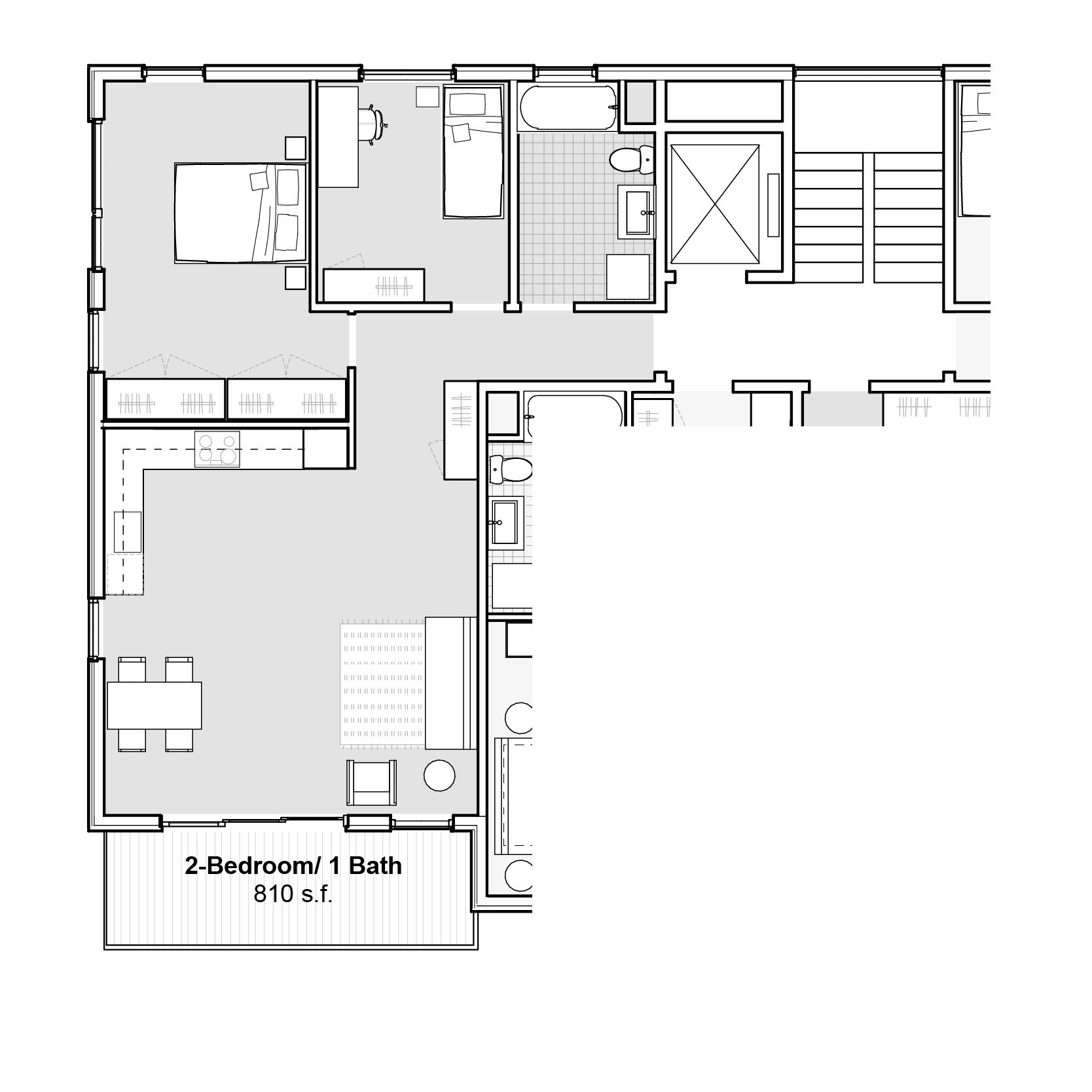

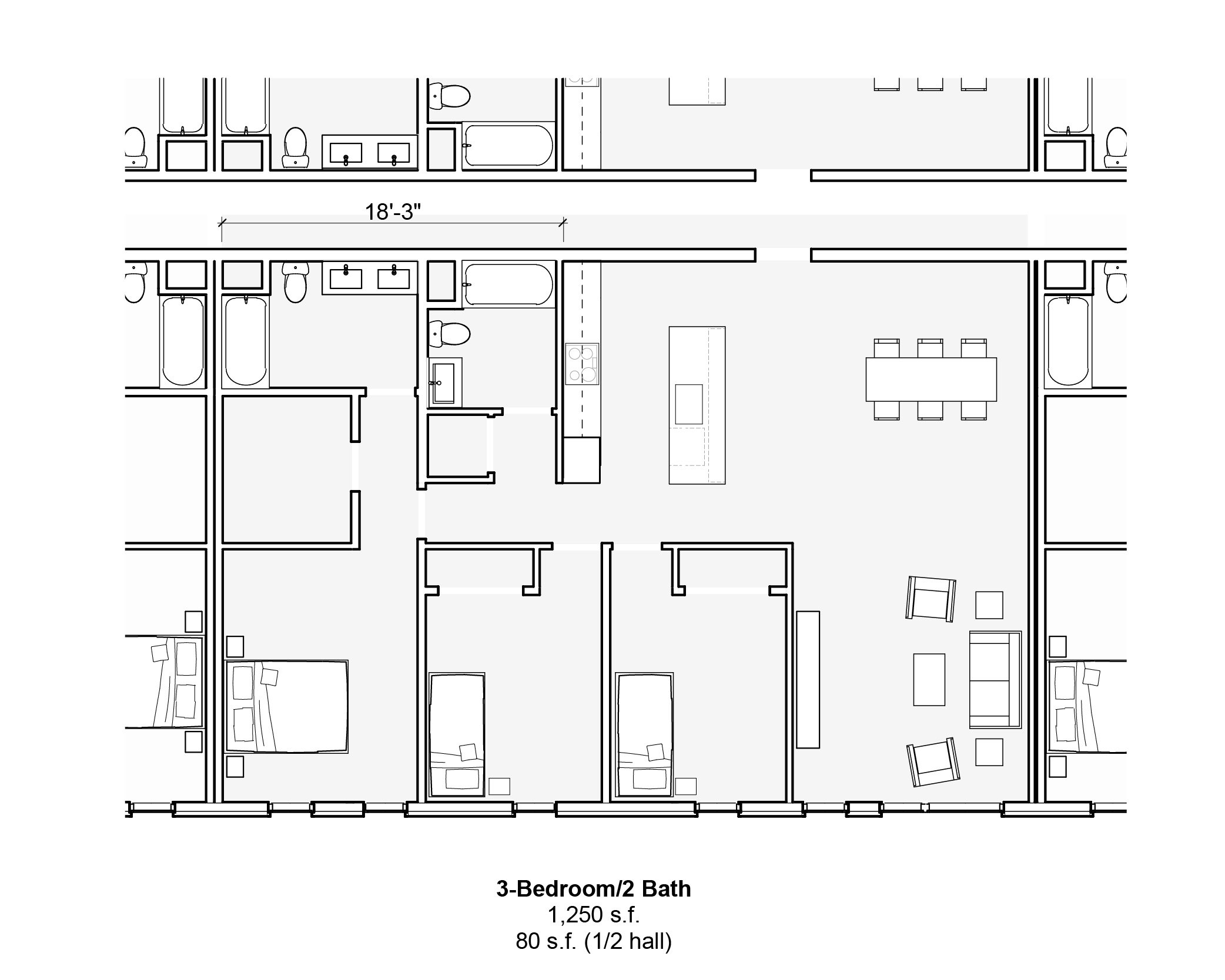

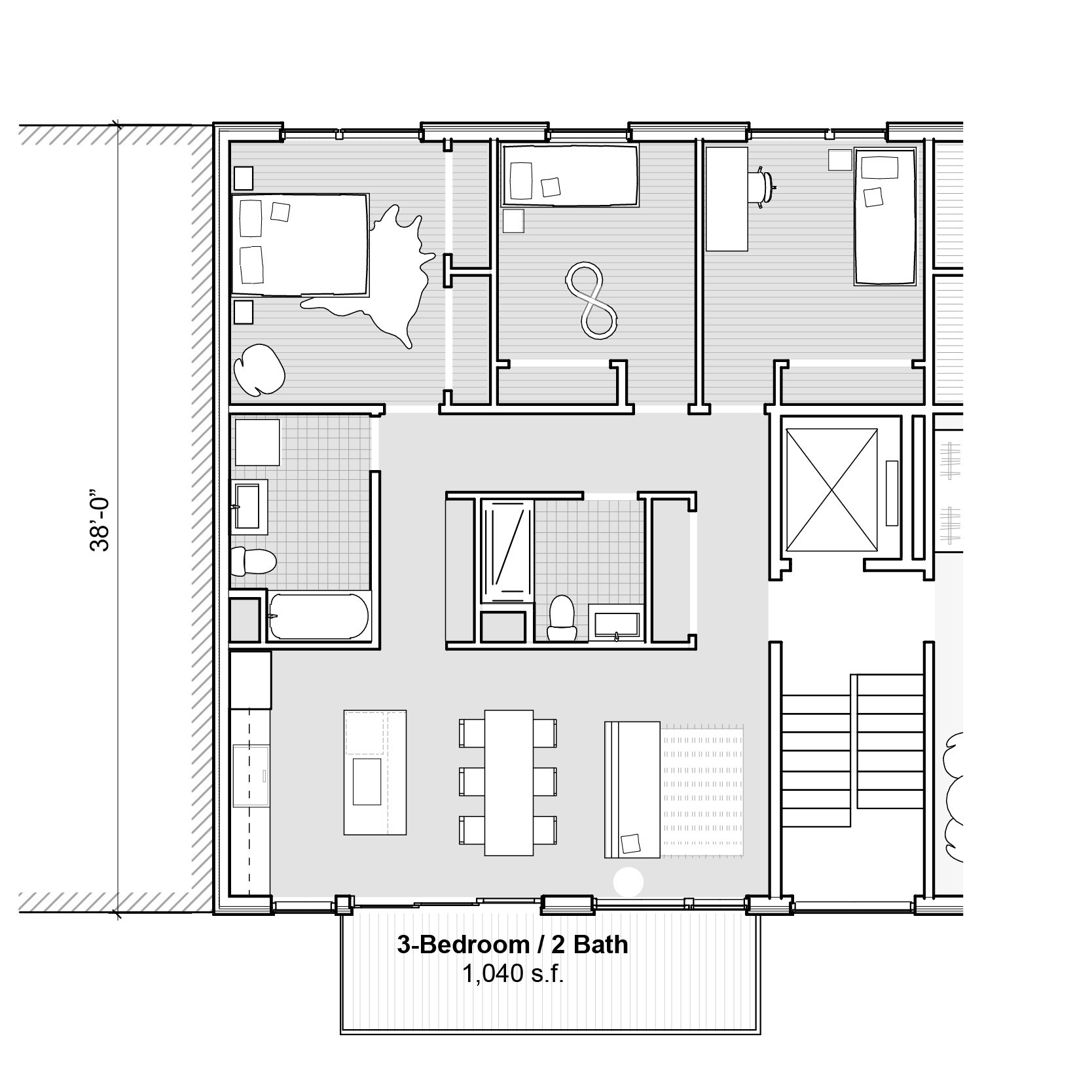

In North America, apartments are typically laid out off of a double-loaded corridor – lots of apartments arrayed on either side of a single long hallway, like in a hotel. Each apartment generally has windows facing only one direction, with the opposite wall up against the hallway, and the other two sides up against other units in the same building. As the site grows, the central corridor is simply stretched out, and more apartments are added off of an even longer hallway. In the case of the typical design that we’re using to illustrate this design (first image, showing a segment of a much larger building), each hallway has 29 feet of space on either side, so each apartment is 29 feet in depth, with windows only on one side.

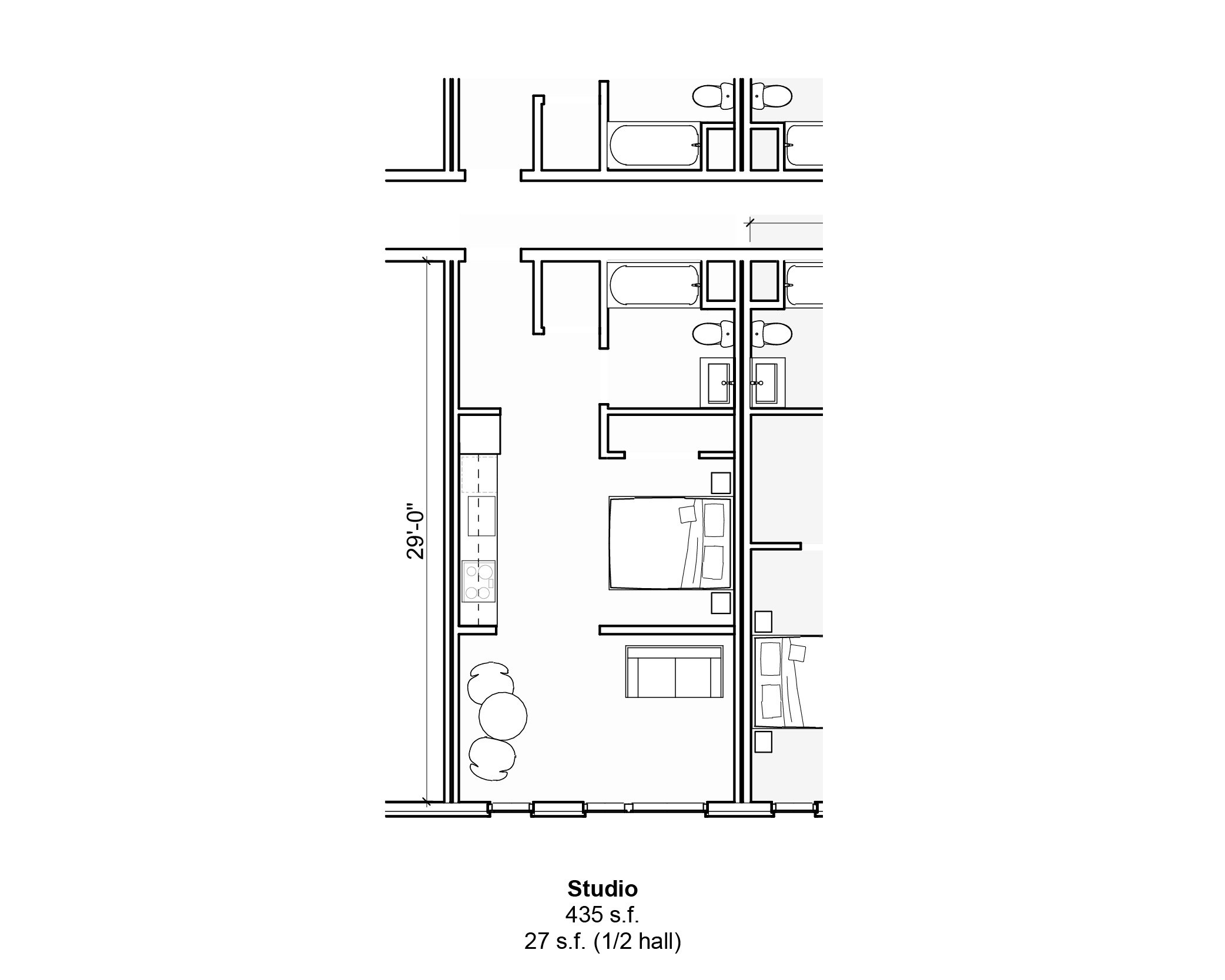

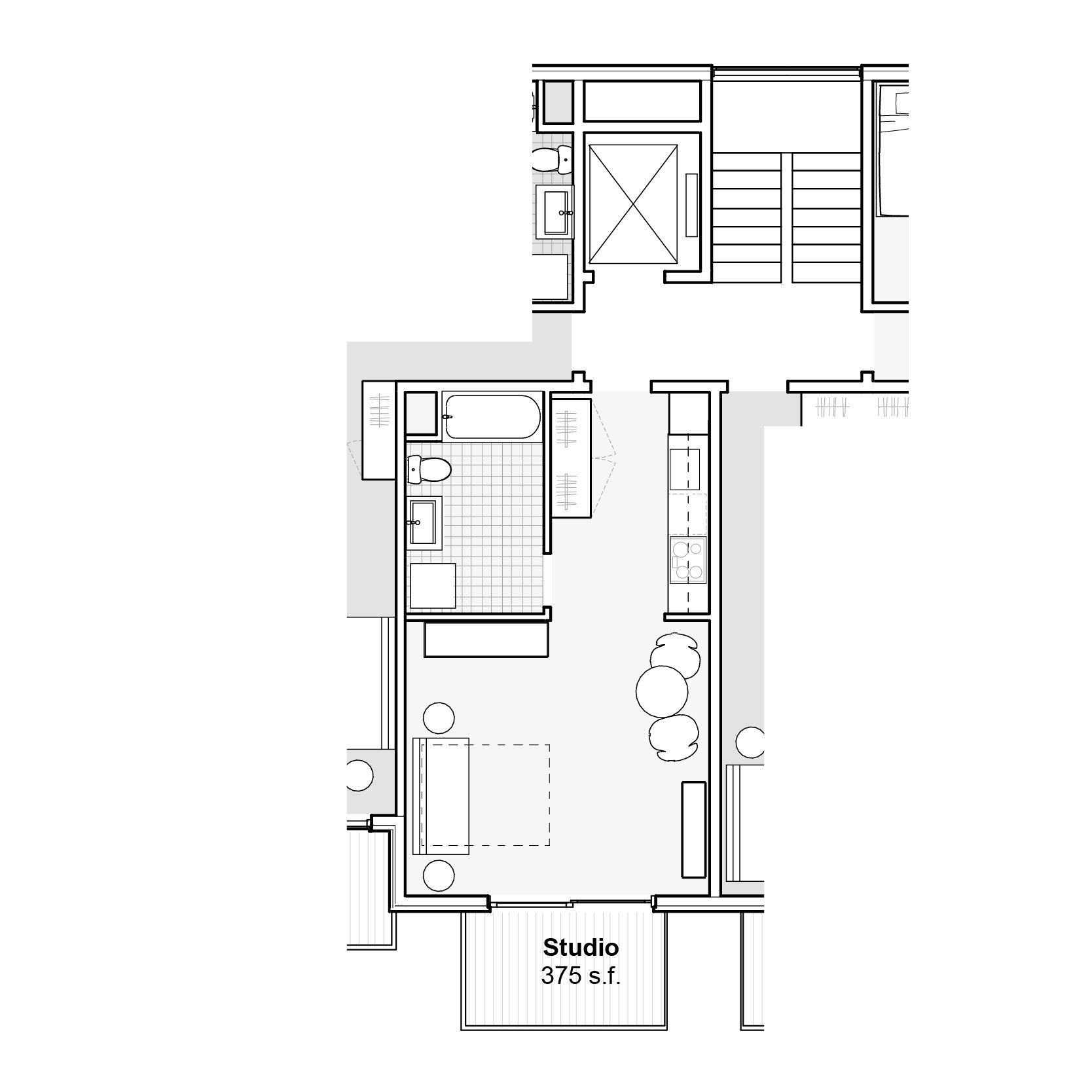

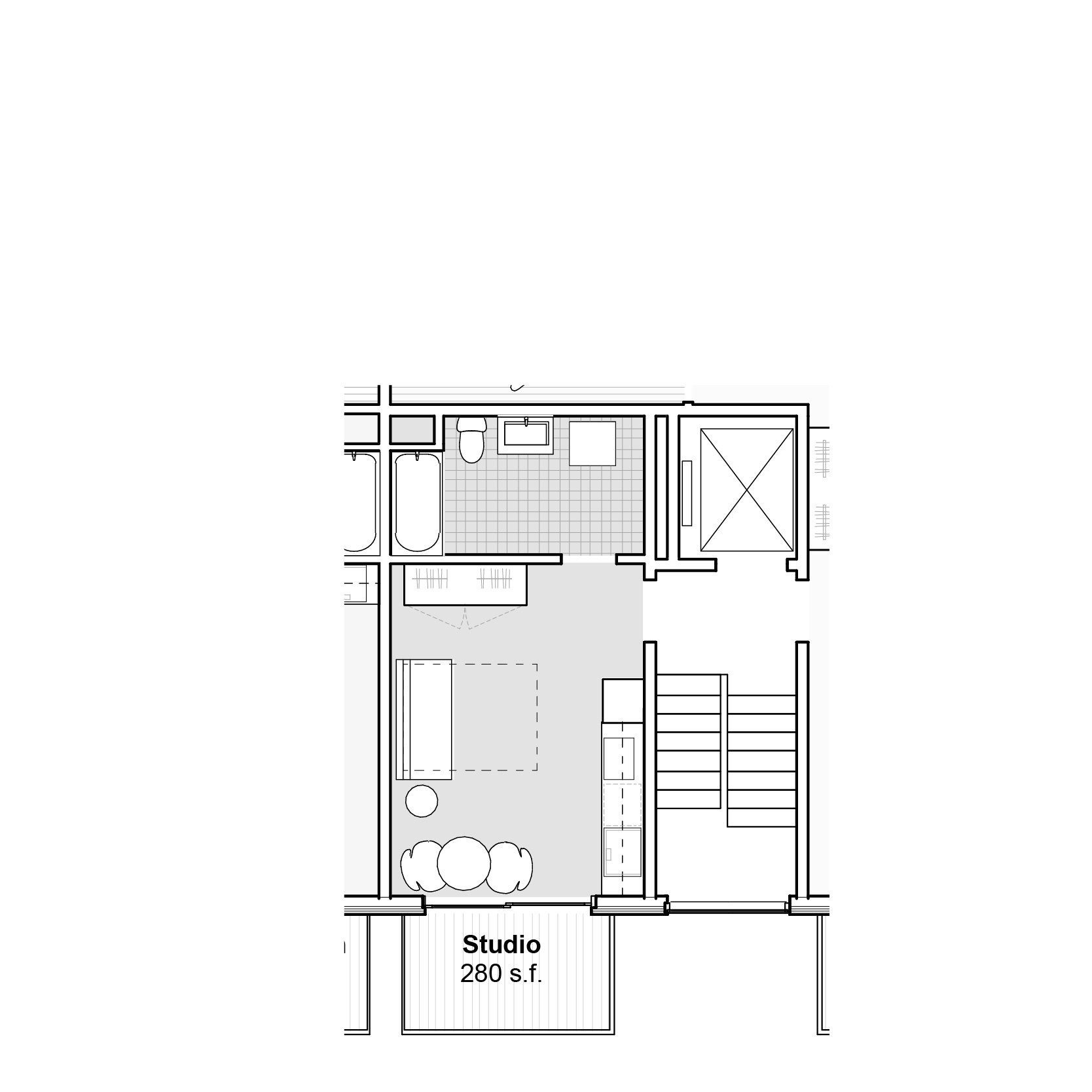

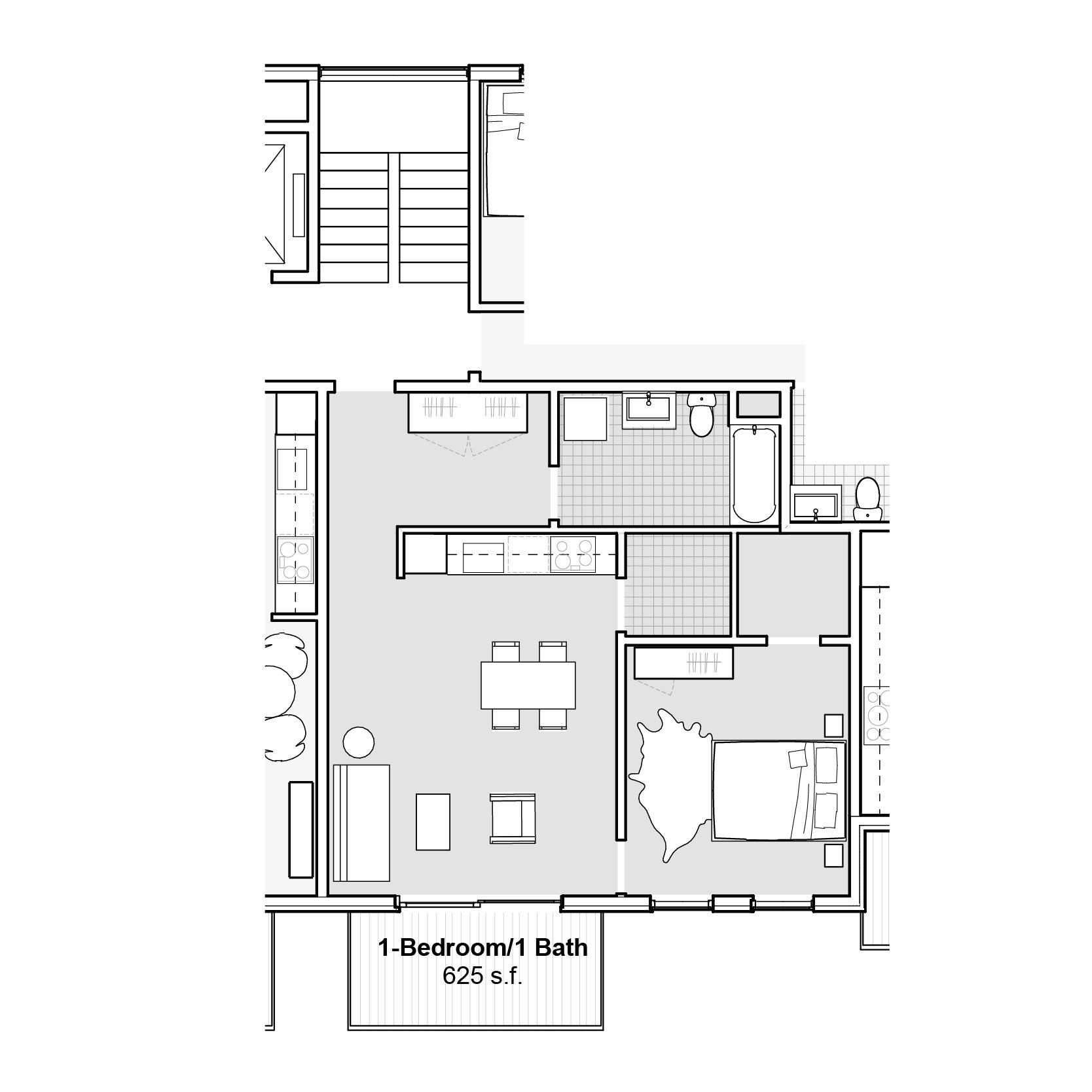

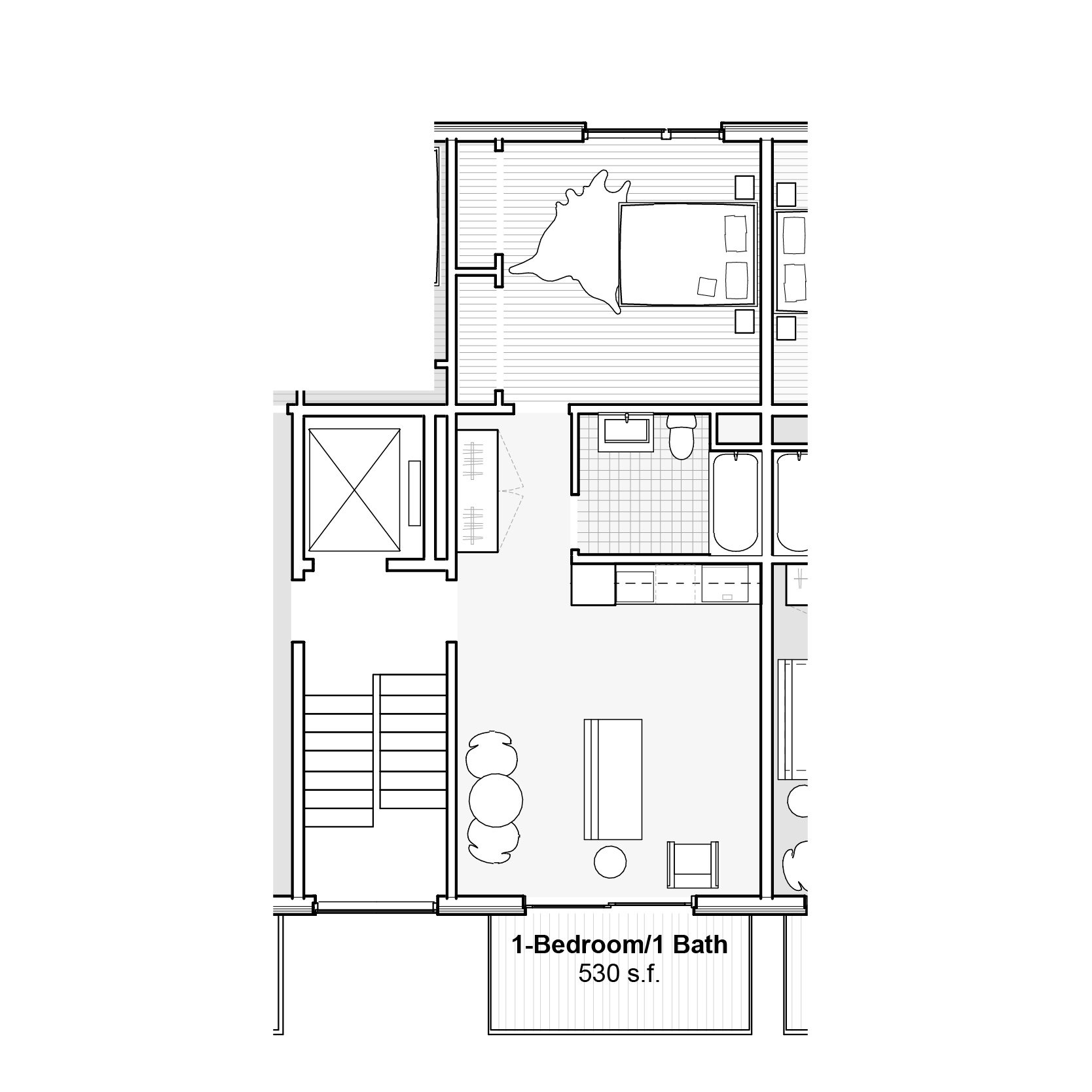

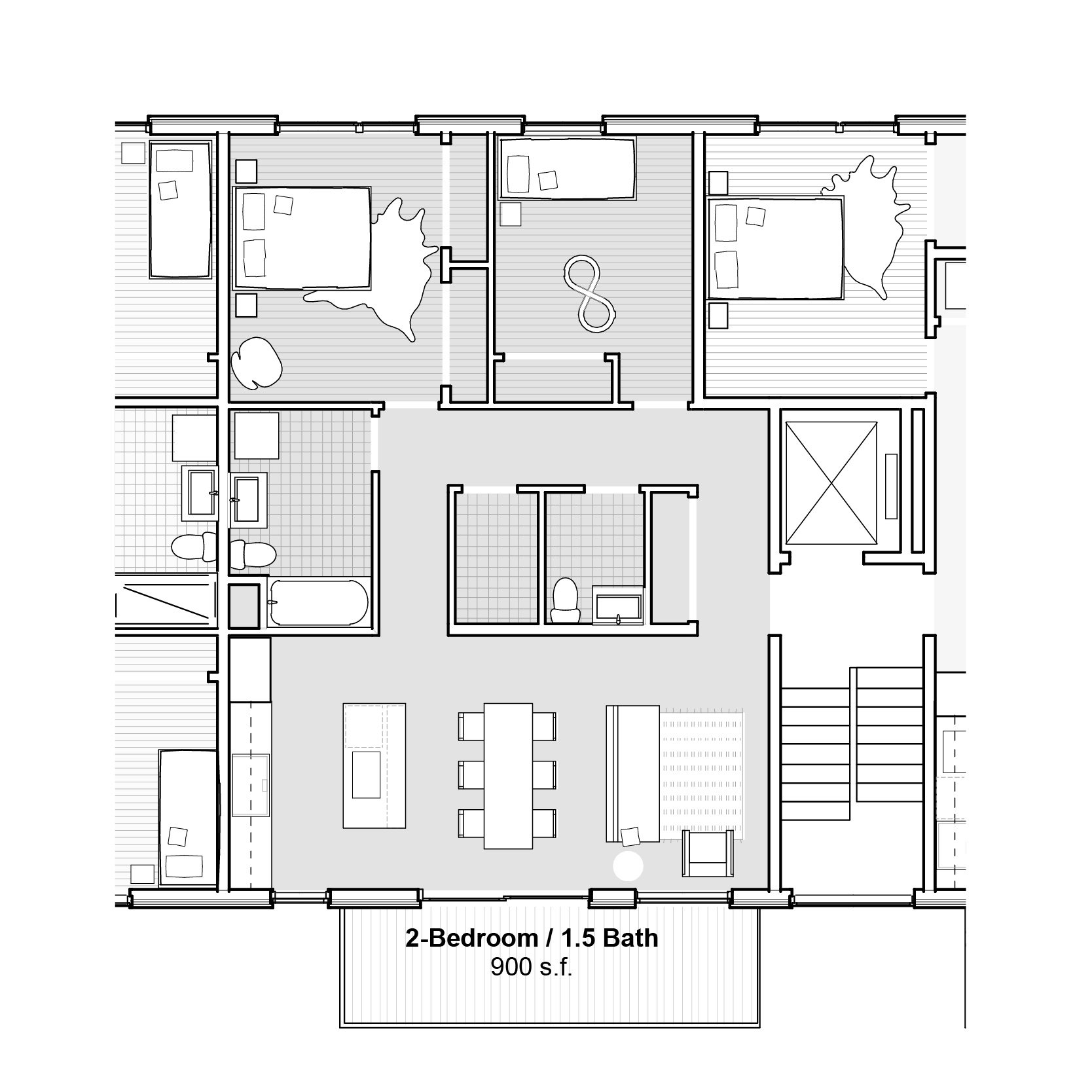

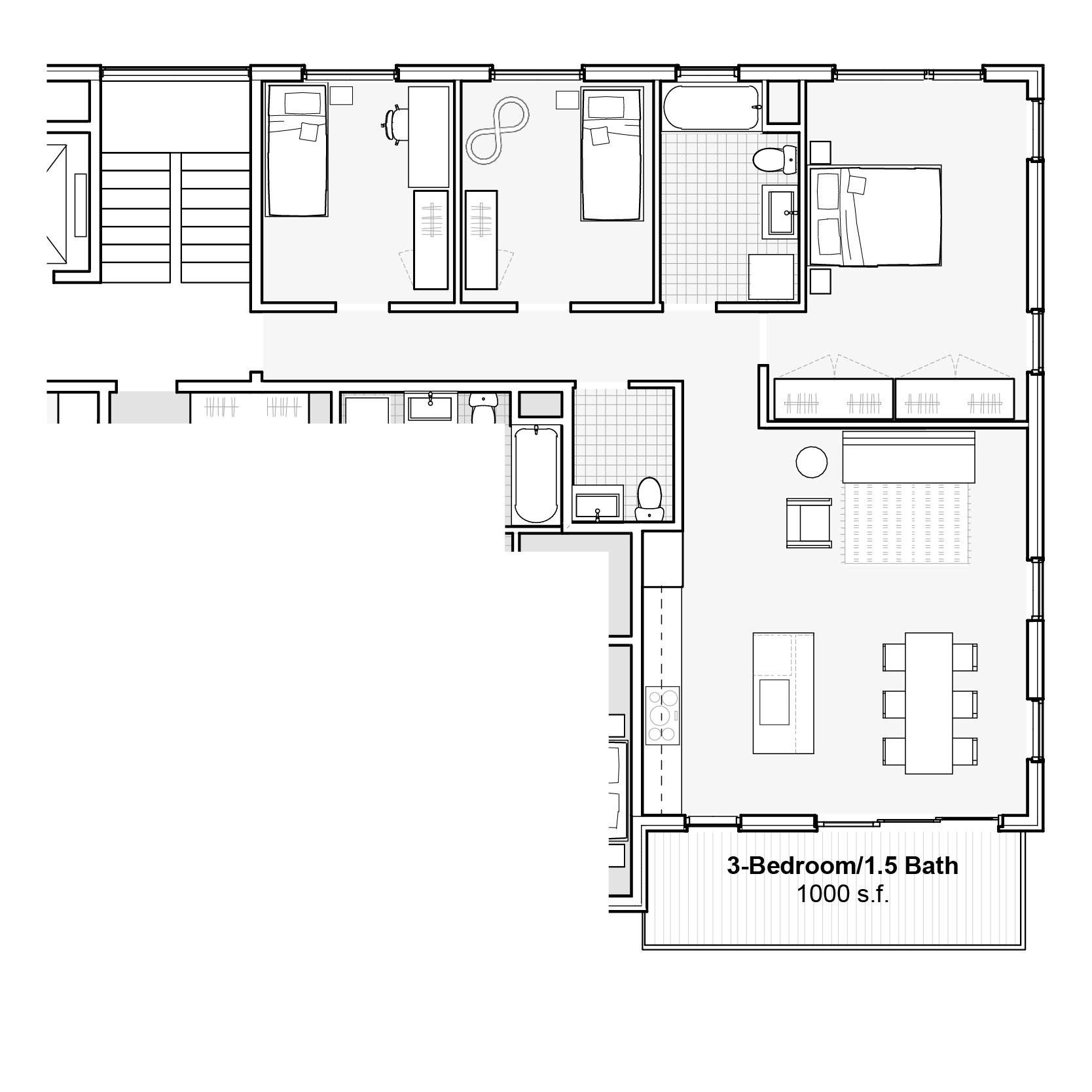

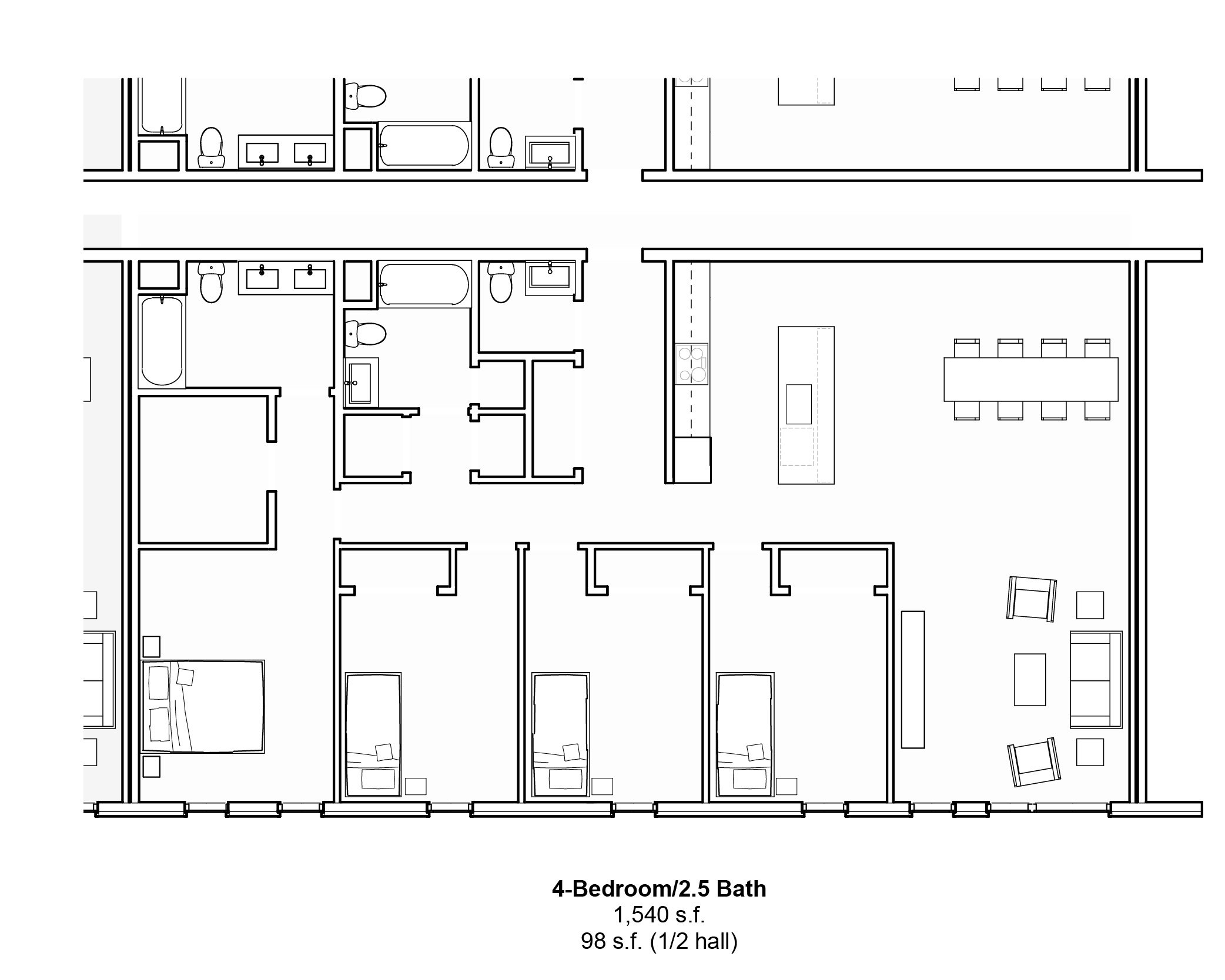

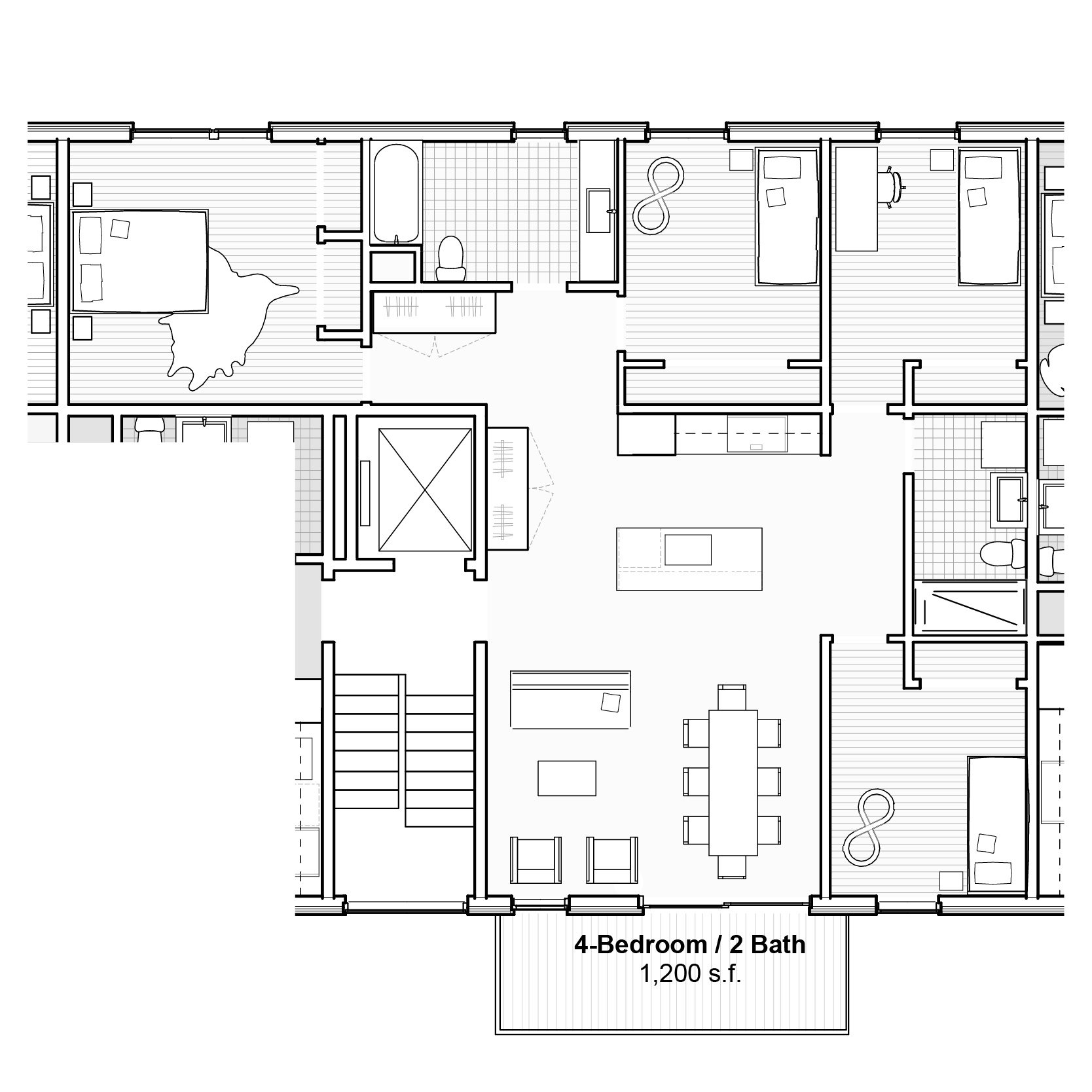

By contrast, in the rest of the world, including in Europe, most new buildings are designed as what Mike Eliason calls point access blocks (second and third plans above) – anywhere between one and generally around six apartments per floor arrayed around a central staircase and, usually, an elevator. Apartments can have windows on opposite sides, because the hallway and other common area take up just a small space near the center of the building. If the site is bigger, this design is repeated a number of times (as in the third image above).

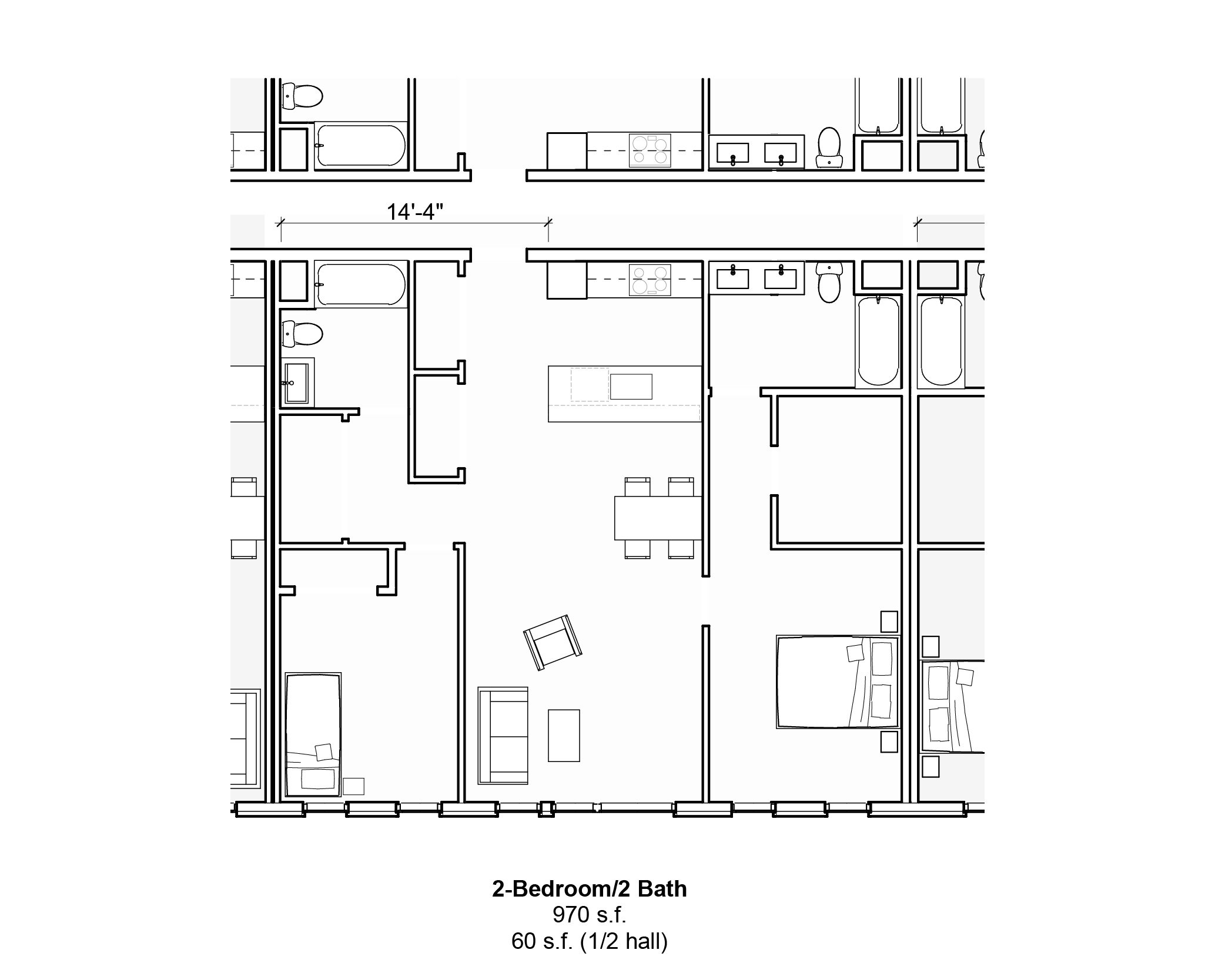

One major consequence of this difference in design is that the North American double-loaded corridor buildings are much worse at providing family-sized units. To illustrate the point, we’ll go through the different sized apartments one by one, and compare the floor area and design. You’ll notice that the American plans have significantly more floor area for the same number of bedrooms, and have much more lightless interior space up against the common corridor to fill – inevitably with bathrooms, closets, and larger kitchens. For families – which tend to be inherently more financially strapped than singles, childless couples, or roommates, since they’re likely to have kids, older adults, and even parents who aren’t working in the household – the cost of all this extra square footage can be too much to bear. The path of least resistance for home seekers is simply to move to the suburbs and buy or rent a freestanding single-family house, where building codes are much looser and zoning affords developers massive tracts of land, so none of this is an issue.

Studio apartments

Starting with a studio, the American design (first unit) can be slightly bigger than a German one (second unit), or significantly bigger (third unit). The 280-sq. ft. micro-studio could not realistically be recreated with a double-loaded corridor design with apartments that are 29 feet deep, since it would require the unit to be less than 10 ft. wide along the windowed wall, making it quite dark.

One-bedroom apartments

The advantages of the shallower European floor plans start to become more apparent with one-bedroom apartments. They allow for a somewhat less deep version of the single-aspect American design (first unit) that’s about 7.5 percent smaller (second unit), or a floor-through design that consumes 21.5 percent fewer square feet (third unit), while also moving the bedroom to the other side of the building, giving the living room and bedroom different sun and noise exposures.

Two-bedroom apartments

At two bedrooms, the flexibility of German layouts becomes obvious. The American plan (first unit) is so deep that each bedroom must necessarily come with its own bathroom (with extra vanity), plus huge walk-in closets. The double vanity bathroom and walk-in closet become marketing points and drive cost and rent up, but are in many cases driven by the need to fill space that can’t be filled with extra living area, and not necessarily the developer and tenants’ desire to spend scarce resources on them. The cost of construction generally rises in lockstep with square footage, but bathrooms and kitchens are particularly expensive given the plumbing and fixtures involved, driving up the cost of production and operations for the standard North American in-line two-bed, two-bath apartment. The American layout also suffers from a “bowling alley” layout, with a narrow common area squeezed between the two bedrooms, offering poor sound separation and privacy.

The German point access block layouts, on the other hand, can offer a much more affordable two-bed, one-bath unit that’s a full 36 percent smaller than the American version (second unit). This could appeal to any number of households: a family with a small child who can’t use the bathroom on their own anyway and with no need for a walk-in closet; a single person or childless couple who needs a home office; or a family of any type who’s on a budget, without the cash to spare for luxuries like a second bathroom and large walk-in closets. The dual-aspect layout also allows the bedrooms to be moved to the other side of the building from the living area, onto a quieter courtyard and away from a TV blaring in the living room.

This 810-sq. ft. two-bed, one-bath also introduces a windowed bathroom. Bathrooms and kitchens with windows are not only expected but mandatory in much of the world, but are almost impossible luxuries in North American apartment buildings, which have to carefully ration their windowed walls and cannot spare them for kitchens and bathrooms.

And then at the other end of the spectrum, the German plan allows for a 2BR/1.5BA (third unit) that’s almost as large as the American version, but with much more light – the living and kitchen areas span a full 26 ft. along a windowed wall. This allows natural ventilation for the kitchen, which could also be walled off into its own room to isolate smells if desired, as is common in most cultures around the world. This version comes with a half-bathroom, which could easily be extended into the adjacent closet to make room for a shower stall or even bathtub, offering two full bathrooms if desired.

Three-bedroom apartments

A European through-floor design (third plan) can save over 200 square feet for a 3BR/2BA apartment compared to the American design (first plan), owing to less lightless space spent on corridors and walk-in closets. With a slight adjustment, the third European design could even have an American-style main bedroom suite, with its own bathroom and the area next to the adjacent bathroom enclosed to form a walk-in closet. A smaller European three-bedroom design (second plan) can also drop half of the second bathroom, saving the cost of an extra fixture and 40 square feet of floor space (that could be over $20,000 in construction, land, and financing costs in an expensive coastal market) for families on tighter budgets, or with younger kids who aren’t spending much time in the bathroom unsupervised anyway.

Four-bedroom apartments

The European 4BR/2BA design (second plan) matches the American 3BR/2BA (first plan, in the prior series) in size and fixtures, and therefore rough cost of construction. That is to say, you can fit four bedrooms in Europe in the space of three bedrooms in America. While new four-bedroom apartments are reasonably common in Europe, a new American four-bedroom apartment is largely theoretical – the cost is so high that they are rarely found in real life. American families instead tend to opt for single-family houses, whether freestanding houses in the suburbs, or attached townhouses in more urban areas. Single-family designs, however, lack the accessibility of elevators and require more maintenance, and tall townhouses in particular tend to be less efficient (and therefore larger) due to staircases consuming more floor area.

The above examples are stylized plans, and the economics of construction are a bit more complicated. Beyond the apartments, there are also hallways, staircases, elevators, lobbies, garages, and other elements to consider. For a double-loaded corridor building, the hallway outside of the unit (measured on the plans below the within-unit square footage) tends to add more square footage; for a point access block, each apartment will have to share the cost of the vertical circulation with fewer other units on that floor. But in general, construction cost tracks the square footage of the unit. And what these plans show is that size – and therefore cost – reductions of up to a third or more are possible with more flexible point access block layouts, which are generally not legal above three stories (or two in Canada).

What drives these differences?

There are two factors driving this difference in design: vertical circulation requirements as dictated by the building code, and the external envelope of the building as dictated by the zoning code.

North American codes (mostly building codes) have much more demanding vertical circulation requirements – that is, stairs, elevators, and in some cases even trash chutes and rooms – than codes in the rest of the world. Two stairs are required instead of one, even at fairly low heights. The stairs are required to be enclosed rather than open to the hall that serves the units. The stair treads must all be perfectly rectangular. The elevator cabins are required to accommodate a wheelchair making a 180-degree turn within them, and also a fully-extended 7-ft. stretcher. Trash is sometimes required to be collected on each floor.

In the rest of the world, many of the above requirements only kick in for high-rises (and sometimes, not even then). For a mid-rise building, one staircase is almost always enough. At lower heights, the staircase can be open to the hall. In some countries (like France), the staircase can have winder treads, saving space. The elevator is required to accommodate a wheelchair and another person standing behind it, but, at least in Europe, typically not a turning radius inside of the cabin. In the rare cases that somebody needs to be taken out of the building in a fully-extended stretcher, without having the head propped up to fit in an elevator that’s 1.4 meters (4 feet, 7 inches) deep, paramedics take the stairs. The result is that in the most of rest of the world, it’s more affordable to simply duplicate the vertical access core as the building grows (as in the third plan in the first set of images), rather than to extend the hallway through the middle and keep adding units on either side.

Beyond building code issues, zoning codes strongly encourage double-loaded corridors in North America. Planning anywhere in the world typically dictates the envelope of buildings with tools like height limits, setback rules, and total floor area limits. In North America, the vast majority of urban residential land is reserved for single-family houses, while apartment buildings are limited to retail corridors, former industrial districts, downtowns, highway frontage, and historical city center multifamily neighborhoods. With proportionally less land in, say, the New York or Toronto areas zoned for apartments than in, for example, Dhaka or Rome, buildings must fill a much larger proportion of their lots to meet growing housing needs. As a result, new apartment buildings in North America end up at least 65 feet thick – leading to units that are around 30 feet deep after the common corridor is subtracted, as illustrated in our American floor plans, which clock in at 29 feet (and often more like 75 or 80 feet). At this depth, there is far too much room to fill for an apartment to stretch from one side the building to the other, even if the building code allowed such a thing. Instead, a double-loaded corridor with ample bathrooms, closets, and kitchen space is the only reasonable way to fill the dark middle of the building.

The only way to make these spaces efficient is to drop the requirement that bedrooms have windows. This makes it possible to fit more bedrooms into a space with limited windowed wall length, but at the expense of light and air. These designs are legal (and increasingly popular) in many American jurisdictions, but are almost unheard of outside of the United States.

A double-loaded corridor building with almost no windows in bedrooms, from Seattle. Image via Mike Eliason.

The merits of North American building and zoning codes can be debated, but the effect is clearly that apartments, in order to provide the same number of bedrooms and give everyone a window, must necessarily consume far more floor area than point access block designs possible in other countries. So if you’re looking for a family-sized apartment in the U.S. or Canada and finding that new buildings don’t have what you’re looking for, it’s not you, it’s not the architect, and it’s not even the developer – it’s the codes.